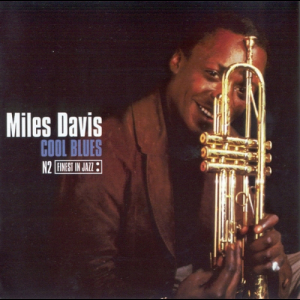

Miles Davis - Cool Blues '1999

| Artist | Miles Davis Related artists |

| Album name | Cool Blues |

| Country | |

| Date | 1999 |

| Genre | Jazz |

| Play time | 47:48 |

| Format / Bitrate | Stereo 1420 Kbps

/ 44.1 kHz MP3 320 Kbps |

| Media | CD |

| Size | 236 Mb |

| Price | Download $1.95 |

Order this album and it will be available for purchase and further download within 12 hours

Pre-order album Tracks list

Tracks list

Tracklist: 01. A Night In Tunisia 02. Embraceable You 03. Yardbird Suite 04. Dont Blame Me 05. My Old Flame 06. Out Of Nowhere 07. Scrapple The Apple 08. Cool Blues 09. Bird Of Paradise 10. Birds Nest 11. Mr. Lucky 12. Moose The Mooche 13. Lovers Theme 14. Ornithology  Throughout a professional career lasting 50 years, Miles Davis played the trumpet in a lyrical, introspective, and melodic style, often employing a stemless Harmon mute to make his sound more personal and intimate. But if his approach to his instrument was constant, his approach to jazz was dazzlingly protean. To examine his career is to examine the history of jazz from the mid-40s to the early 90s, since he was in the thick of almost every important innovation and stylistic development in the music during that period, and he often led the way in those changes, both with his own performances and recordings and by choosing sidemen and collaborators who forged new directions. It can even be argued that jazz stopped evolving when Davis wasnt there to push it forward. Davis was the son of a dental surgeon, Dr. Miles Dewey Davis, Jr., and a music teacher, Cleota Mae (Henry) Davis, and grew up in the black middle class of East St. Louis after the family moved there shortly after his birth. He became interested in music during his childhood and by the age of 12 began taking trumpet lessons. While still in high school, he started to get jobs playing in local bars and at 16 was playing gigs out of town on weekends. At 17, he joined Eddie Randles Blue Devils, a territory band based in St. Louis. He enjoyed a personal apotheosis in 1944, just after graduating from high school, when he saw and was allowed to sit in with Billy Eckstines big band, which was playing in St. Louis. The band featured trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie and saxophonist Charlie Parker, the architects of the emerging bebop style of jazz, which was characterized by fast, inventive soloing and dynamic rhythm variations. Birth of the Cool It is striking that Davis fell so completely under Gillespie and Parkers spell, since his own slower and less flashy style never really compared to theirs. But bebop was the new sound of the day, and the young trumpeter was bound to follow it. He did so by leaving the Midwest to attend the Institute of Musical Art in New York City (renamed Juilliard) in September 1944. Shortly after his arrival in Manhattan, he was playing in clubs with Parker, and by 1945 he had abandoned his academic studies for a full-time career as a jazz musician, initially joining Benny Carters band and making his first recordings as a sideman. He played with Eckstine in 1946-1947 and was a member of Parkers group in 1947-1948, making his recording debut as a leader on a 1947 session that featured Parker, pianist John Lewis, bassist Nelson Boyd, and drummer Max Roach. This was an isolated date, however, and Davis spent most of his time playing and recording behind Parker. But in the summer of 1948, he organized a nine-piece band with an unusual horn section. In addition to himself, it featured an alto saxophone, a baritone saxophone, a trombone, a French horn, and a tuba. This nonet, employing arrangements by Gil Evans and others, played for two weeks at the Royal Roost in New York in September. Earning a contract with Capitol Records, the band went into the studio in January 1949 for the first of three sessions and produced 12 tracks that attracted little attention at first. The bands relaxed sound, however, affected the musicians who played it, among them Kai Winding, Lee Konitz, Gerry Mulligan, John Lewis, J.J. Johnson, and Kenny Clarke, and it had a profound influence on the development of the cool jazz style on the West Coast. (In February 1957, Capitol finally issued the tracks together on an LP called Birth of the Cool.) Round About MidnightDavis, meanwhile, had moved on to co-leading a band with pianist Tadd Dameron in 1949, and the group took him out of the country for an appearance at the Paris Jazz Festival in May. But the trumpeters progress was impeded by an addiction to heroin that plagued him in the early 50s. His performances and recordings became more haphazard, but in January 1951 he began a long series of recordings for the Prestige label that became his main recording outlet for the next several years. He managed to kick his habit by the middle of the decade, and he made a strong impression playing Round Midnight at the Newport Jazz Festival in July 1955, a performance that led major-label Columbia to sign him. The prestigious contract allowed him to put together a permanent band, and he organized a quintet featuring saxophonist John Coltrane, pianist Red Garland, bassist Paul Chambers, and drummer Philly Joe Jones, who began recording his Columbia debut, Round About Midnight, in October. The New Miles Davis Quintet As it happened, however, he had a remaining five albums on his Prestige contract, and over the next year he was forced to alternate his Columbia sessions with sessions for Prestige to fulfill this previous commitment. The latter resulted in the Prestige albums The New Miles Davis Quintet, Cookin, Workin, Relaxin, and Steamin, making Davis first quintet one of his better-documented outfits. In May 1957, just three months after Capitol released the Birth of the Cool LP, Davis again teamed with arranger Gil Evans for his second Columbia LP, Miles Ahead. Playing flügelhorn, Davis fronted a big band on music that extended the Birth of the Cool concept and even had classical overtones. Released in 1958, the album was later inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame, intended to honor recordings made before the Grammy Awards were instituted in 1959. L Ascenseur Pour Lechafaud [Original Soundtrack] In December 1957, Davis returned to Paris, where he improvised the background music for the film LAscenseur pour lEchafaud. Jazz Track, an album containing this music, earned him a 1960 Grammy nomination for Best Jazz Performance, Solo or Small Group. He added saxophonist Cannonball Adderley to his group, creating the Miles Davis Sextet, which recorded Milestones in April 1958. Shortly after this recording, Red Garland was replaced on piano by Bill Evans and Jimmy Cobb took over for Philly Joe Jones on drums. In July, Davis again collaborated with Gil Evans and an orchestra on an album of music from Porgy and Bess. Back in the sextet, Davis began to experiment with modal playing, basing his improvisations on scales rather than chord changes. Kind of Blue This led to his next band recording, Kind of Blue, in March and April 1959, an album that became a landmark in modern jazz and the most popular album of Davis career, eventually selling over two million copies, a phenomenal success for a jazz record. In sessions held in November 1959 and March 1960, Davis again followed his pattern of alternating band releases and collaborations with Gil Evans, recording Sketches of Spain, containing traditional Spanish music and original compositions in that style. The album earned Davis and Evans Grammy nominations in 1960 for Best Jazz Performance, Large Group, and Best Jazz Composition, More Than 5 Minutes; they won in the latter category. Someday My Prince Will Come By the time Davis returned to the studio to make his next band album in March 1961, Adderley had departed, Wynton Kelly had replaced Bill Evans at the piano, and John Coltrane had left to begin his successful solo career, being replaced by saxophonist Hank Mobley (following the brief tenure of Sonny Stitt). Nevertheless, Coltrane guested on a couple of tracks of the album, called Someday My Prince Will Come. The record made the pop charts in March 1962, but it was preceded into the best-seller lists by the Davis quintets next recording, the two-LP set Miles Davis in Person (Friday & Saturday Nights at the Blackhawk, San Francisco), recorded in April. The following month, Davis recorded another live show, as he and his band were joined by an orchestra led by Gil Evans at Carnegie Hall in May. The resulting Miles Davis at Carnegie Hall was his third LP to reach the pop charts, and it earned Davis and Evans a 1962 Grammy nomination for Best Jazz Performance by a Large Group, Instrumental. Davis and Evans teamed up again in 1962 for what became their final collaboration, Quiet Nights. The album was not issued until 1964, when it reached the charts and earned a Grammy nomination for Best Instrumental Jazz Performance by a Large Group or Soloist with Large Group. Miles Davis and Gil Evans: The Complete Columbia Studio Recordings In 1996, Columbia Records released a six-CD box set, Miles Davis & Gil Evans: The Complete Columbia Studio Recordings, that won the Grammy for Best Historical Album. Quiet Nights was preceded into the marketplace by Davis next band effort, Seven Steps to Heaven, recorded in the spring of 1963 with an entirely new lineup consisting of saxophonist George Coleman, pianist Victor Feldman, bassist Ron Carter, and drummer Frank Butler. During the sessions, Feldman was replaced by Herbie Hancock and Butler by Tony Williams. The album found Davis making a transition to his next great group, of which Carter, Hancock, and Williams would be members. It was another pop chart entry that earned 1963 Grammy nominations for both Best Instrumental Jazz Performance by a Soloist or Small Group and Best Instrumental Jazz Performance by a Large Group. The quintet followed with two live albums, Miles Davis in Europe, recorded in July 1963, which made the pop charts and earned a 1964 Grammy nomination for Best Instrumental Jazz Performance by a Small Group or Soloist with Small Group, and My Funny Valentine, recorded in February 1964 and released in 1965, when it reached the pop charts. E.S.P. By September 1964, the final member of the classic Miles Davis Quintet of the 60s was in place with the addition of saxophonist Wayne Shorter to the team of Davis, Carter, Hancock, and Williams. While continuing to play standards in concert, this unit embarked on a series of albums of original compositions contributed by the bandmembers themselves, starting in January 1965 with E.S.P., followed by Miles Smiles (1967 Grammy nomination for Best Instrumental Jazz Performance by a Small Group or Soloist with Small Group [7 or Fewer]), Sorcerer, Nefertiti, Miles in the Sky (1968 Grammy nomination for Best Instrumental Jazz Performance by a Small Group or Soloist with Small Group), and Filles de Kilimanjaro. By the time of Miles in the Sky, the group had begun to turn to electric instruments, presaging Davis next stylistic turn. By the final sessions for Filles de Kilimanjaro in September 1968, Hancock had been replaced by Chick Corea and Carter by Dave Holland. But Hancock, along with pianist Joe Zawinul and guitarist John McLaughlin, participated on Davis next album, In a Silent Way (1969), which returned the trumpeter to the pop charts for the first time in four years and earned him another small-group jazz performance Grammy nomination. With his next album, Bitches Brew, Davis turned more overtly to a jazz-rock style. Though certainly not conventional rock music, Davis electrified sound attracted a young, non-jazz audience while putting off traditional jazz fans. Miles Davis at Fillmore: Live at the Fillmore EastBitches Brew, released in March 1970, reached the pop Top 40 and became Davis first album to be certified gold. It also earned a Grammy nomination for Best Instrumental Arrangement and won the Grammy for large-group jazz performance. He followed it with such similar efforts as Miles Davis at Fillmore East (1971 Grammy nomination for Best Jazz Performance by a Group), A Tribute to Jack Johnson, Live-Evil, On the Corner, and In Concert, all of which reached the pop charts. Meanwhile, Davis former sidemen became his disciples in a series of fusion groups: Corea formed Return to Forever, Shorter and Zawinul led Weather Report, and McLaughlin and former Davis drummer Billy Cobham organized the Mahavishnu Orchestra. Starting in October 1972, when he broke his ankles in a car accident, Davis became less active in the early 70s, and in 1975 he gave up recording entirely due to illness, undergoing surgery for hip replacement later in the year. Five years passed before he returned to action by recording The Man with the Horn in 1980 and going back to touring in 1981. We Want Miles By now, he was an elder statesman of jazz, and his innovations had been incorporated into the music, at least by those who supported his eclectic approach. He was also a celebrity whose appeal extended far beyond the basic jazz audience. He performed on the worldwide jazz festival circuit and recorded a series of albums that made the pop charts, including We Want Miles (1982 Grammy Award for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance by a Soloist), Star People, Decoy, and Youre Under Arrest. In 1986, after 30 years with Columbia, he switched to Warner Bros. and released Tutu, which won him his fourth Grammy for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance. AuraAura, an album he had recorded in 1984, was released by Columbia in 1989 and brought him his fifth Grammy for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance by a Soloist (on a Jazz Recording). Davis surprised jazz fans when, on July 8, 1991, he joined an orchestra led by Quincy Jones at the Montreux Jazz Festival to perform some of the arrangements written for him in the late 50s by Gil Evans; he had never previously looked back at an aspect of his career. He died of pneumonia, respiratory failure, and a stroke within months. Doo-Bop, his last studio album, appeared in 1992. It was a collaboration with rapper Easy Mo Bee, and it won a Grammy for Best Rhythm & Blues Instrumental Performance, with the track Fantasy nominated for Best Jazz Instrumental Solo. Released in 1993, Miles & Quincy Live at Montreux won Davis his seventh Grammy for Best Large Jazz Ensemble Performance. Everythings BeautifulMiles Davis took an all-inclusive, constantly restless approach to jazz that had begun to fall out of favor by the time of his death, even as it earned him controversy during his lifetime. It was hard to recognize the bebop acolyte of Charlie Parker in the flamboyantly dressed leader with the hair extensions who seemed to keep one foot on a wah-wah pedal and one hand on an electric keyboard in his later years. But he did much to popularize jazz, reversing the trend away from commercial appeal that bebop started. And whatever the fripperies and explorations, he retained an ability to play moving solos that endeared him to audiences and demonstrated his affinity with tradition. He is a reminder of the musics essential quality of boundless invention, using all available means. Twenty-four years after Davis death, he was the subject of Miles Ahead, a biopic co-written and directed by Don Cheadle, who also portrayed him. Its soundtrack functioned as a career overview with additional music provided by pianist Robert Glasper and associates. Additionally, Glasper enlisted many of his collaborators to help record Everythings Beautiful, a separate release that incorporated Davis master recordings and outtakes into new compositions.

Related artists

Miles Davis

Album

- September 27, 1960 - May 29, 1963 Manchester Concert: Complete 1960 Live at the Free Trade Hall

- Mar. 20th, 1960 Olympia : Mar. 20th, 1960

- June 1963 Miles In St. Louis

- June 15, 2004 Jazz Moods: Cool

- January 26, 1984 - January, 1985 Youre Under Arrest

- France, July 25th, 1969 Festiva De Juan Pins

- February 12, 1964 New York City, Philharmonic Hall At Lincoln Center, February 12, 1964

- BDMUSIC BD Music Presents: Miles Davis

- April 9, 1960 - October 15, 1960 So What (The Complete 1960 Amsterdam Concerts)

- 2024 INTEGRAL MILES DAVIS 1951-1956

- 2024 Melodie Originale (Live Paris '73)

- 2023 Turnaround: Rare Miles From The Complete On The Corner Sessions

- 2023 A Catalogue of Jazz: Miles Davis

- 2023 Bye Bye Blackbird

- 2023 Fearless (March 7, 1970 Live At The Fillmore East)

- 2023 Miles Davis - Jazz Masters Deluxe

- 2023 Miles Davis Anthology, Vol. 1

- 2023 Miles Davis Anthology, Vol. 2

- 2023 Miles Davis With Tadd Dameron Revisited

- 2023 Milestar

- 2023 The Electric Years

- 2023 Tivoli Koncertsal (Live Copenhagen '71)

- 2022 Four Classic Albums (Quintet - Sextet / Bags’ Groove / Miles / Miles Davis & the Modern Jazz Giants) (Digitally Remastered)

- 2022 Jazz Legends: Miles Davis

- 2022 Kind of Blue: Modern Jazz's Holy Grail

- 2022 Miles Davis Hits and Rarities

- 2022 That’s What Happened 1982–1985: The Bootleg Series, Vol. 7

- 2022 The Finest

- 2021 Champions (Rare Miles From The Complete Jack Johnson Sessions)

- 2021 A Touch Of Blue

- 2021 BD Music Presents Kind of Blue [2]

- 2021 Caught Up In Circles (Live 1990)

- 2021 Greatest Hits of Miles Davis

- 2021 Masters of Jazz Presents: Miles Davis (1951 - 1959 The Essential Works)

- 2021 Miles Davis Jazz Monument

- 2021 The Absolutely Essential

- 2021 The Lost Concert

- 2020 Music From And Inspired By The Film Birth Of The Cool [2]

- 2020 Double Image: Rare Miles From The Complete Bitches Brew Sessions

- 2020 Music From and Inspired by The Film Birth Of The Cool

- 2020 Anthology 2020 (All Tracks Remastered)

- 2020 Before The Cool: The Miles Davis Collection 1945-48

- 2020 Miles Davis At Newport 1955-1975: The Bootleg Series Vol. 4

- 2020 Miles Davis FM Broadcast August 1990

- 2020 The Lost Septet

- 2019 Rubberband [2]

- 2019 The Lost Quintet

- 2019 Autumn in Paris?

- 2019 1951-1959 The Essential Works

- 2019 1960: Live and Remastered

- 2019 Best of Electric Live

- 2019 Complete Blue Note 1952-1954 Studio Sessions (Bonus Track Version)

- 2019 Ice And Cream

- 2019 Miles Davis and his favorite Tenors, Vol. 1-10

- 2019 Original Jazz Movie Soundtracks, Vol. 1-10

- 2019 Rare and Unreleased

- 2019 The Picasso of Jazz

- 2019 Three Classic Albums Plus

- 2018 Best Of Live 1986-91

- 2018 The Classic Collaborations 1953-1963

- 2017 All The Best

- 2017 The Complete 1961 Carnegie Hall Recordings

- 2017 The Complete in Person Friday and Saturday Nights at the Blackhawk Recordings (Remastered Edition, L

- 2016 Great 5: Round About Midnight (Mono)

- 2016 Great 5: Milestones (Mono)

- 2016 Porgy And Bess

- 2016 Sketches Of Spain

- 2016 Miles Smiles

- 2016 Kind Of Blue

- 2016 5 Original Albums

- 2016 Freedom Jazz Dance: The Bootleg Series, Vol. 5

- 2016 Great 5

- 2016 Legrand Jazz

- 2016 Miles Deep

- 2016 Transmission Impossible (Live)

- 2015 Miles + Miles

- 2015 The Last Word: The Warner Bros. Years, Part 1

- 2015 The Last Word: The Warner Bros. Years, Part 2

- 2015 Miles Davis Quintessence, Vol. 2: New York Paris 1954-1960

- 2015 Sun Palace, Fukuoka, Japan October 81

- 2015 The Last Word: The Warner Bros. Years

- 2014 Black Beauty At Fillmore West

- 2014 At The Fillmore [2]

- 2014 Live at the Fillmore 1970: The Bootleg Series, Vol. 3

- 2014 So What?

- 2013 So What. The Complete 1960 Amsterdam Concerts (CD1)

- 2013 So What. The Complete 1960 Amsterdam Concerts (CD2)

- 2013 Four Classic Albums (Miles Ahead / Sketches of Spain / Porgy and Bess / Ascenseur Pour l'Echafaud)

- 2013 North Sea Jazz Legendary Concerts

- 2013 The Original Mono Recordings

- 2012 Many Miles Of Davis / Pres’

- 2012 Miles Davis Plays for Lovers

- 2011 On The Crest Of The Airwaves [2]

- 2011 The Real... Miles Davis (3CD)

- 2011 1986-1991: The Warner Years (CD5) (5 BOX CD Set)

- 2011 1986-1991: The Warner Years (CD4) (5 BOX CD Set)

- 2011 1986-1991: The Warner Years (CD3) (5 BOX CD Set)

- 2011 1986-1991: The Warner Years (CD2) (5 BOX CD Set)

- 2011 1986-1991: The Warner Years (CD1) (5 BOX CD Set)

- 2011 The Definitive Miles Davis On Prestige (2CD)

- 2011 The Original 1959 Mono Kind Of Blue Recordings, Disc 8

- 2011 The Jazz At The Plaza And 1961 Studio Recordings, Disc 6

- 2011 The Complete 1959 Stereo Kind Of Blue Sessions, Disc 5

- 2011 The 1958 Stereo Jazz Track And Newport Recordings, Disc 4

- 2011 Chasin The Trane

- 2011 The Unissued Japanese Concerts

- 2010 Original Album Classics [5CD]

- 2010 Going Miles

- 2010 The Mellow Sound Of Miles Davis

- 2010 Live At The Blue Coronet 1969 (2CD)

- 2010 Bitches Brew - 40th Anniversary Legacy Edition (2CD)

- 2010 Live At Newport 1966 & 1967

- 2010 Original Albums Classics

- 2009/2012 Enigma, The Complete Blue Note Sessions 1952-1953

- 2009 Sketches Of Spain (50th Anniversary Legacy Edition) (cd1)

- 2009 Miles: The New Miles Davis Quintet

- 2008 Jazz Track

- 2008 Platinum

- 2008 BD Music Presents: Miles Davis, Vol. 2

- 2008 Muted Miles

- 2007 The Very Best Of Miles Davis - The Warner Bros. Sessions 1985 - 1991

- 2007 Miles Davis

- 2007 Miles' Groove

- 2007 The Complete On The Corner Sessions [8]

- 2007 The Complete On The Corner Sessions (disc 1)

- 2007 The Complete On The Corner Sessions (disc 2)

- 2007 The Complete On The Corner Sessions (disc 3)

- 2007 The Complete On The Corner Sessions (disc 4)

- 2007 The Complete On The Corner Sessions (disc 5)

- 2007 The Complete On The Corner Sessions (disc 6)

- 2007 The Complete On The Corner Sessions

- 2007 The Complete On The Corner Sessions

- 2007 Live In Milan 1964

- 2007 The Doo-Bop Song

- 2006 Winter In Europe 1967

- 2006 European Tour '56 With The Modern Jazz Quartet & Lester Young

- 2006 Dig (10-CD Wallet Box CD1)

- 2006 The Serpent's Tooth (10-CD Wallet Box CD2)

- 2006 Tune Up (10-CD Wallet Box CD3)

- 2006 Walkin' (10-CD Wallet Box CD4)

- 2006 Green Haze (10-CD Wallet Box CD5)

- 2006 No Line (10-CD Wallet Box CD6)

- 2006 Just Squeeze Me [2]

- 2006 Bye Bye Blackbird (10-CD Wallet Box CD8)

- 2006 My Funny Valentine (10-CD Wallet Box CD10)

- 2006 Cool & Collected : The Very Best Of Miles Davis

- 2006 Deep Brew Vol. 1 & 2

- 2006 Great Sessions

- 2006 Miles Davis Quintessence 1945-1951

- 2006 The Cellar Door Sessions 1970

- 2006 The Miles Davis Collection

- 2006 The Original Jacket Collection

- 2006 Workin

- 2005 Morpheus - Cd 1

- 2005 Morpheus - Cd 2

- 2005 Morpheus - Cd 3

- 2005 A Tribute To Jack Johnson

- 2005 Poetics Of Sound 1954-1959

- 2004 The Complete Bitches Brew Sessions Disc 1

- 2004 The Complete Bitches Brew Sessions Disc 2

- 2004 The Complete Bitches Brew Sessions Disc 3

- 2004 The Complete Bitches Brew Sessions Disc 4

- 2004 Collectors' Items

- 2004 Seven Steps:complete Recordings

- 2004 Seven Steps Complete Recordings (CD6)

- 2004 Seven Steps Complete Recordings (CD5)

- 2004 Seven Steps Complete Recordings (CD7)

- 2004 Enigma

- 2004 Birdland 1951

- 2004 Serpents Tooth

- 2004 The Best Of Cool

- 2003 The Complete Jack Johnson Sessions (CD 4)

- 2003 In Person At The Blackhawk Friday Night

- 2003 In Person At The Blackhawk Saturday Night

- 2003 Mile Stone

- 2002 Bitches Brew

- 2002 Gold Collection

- 2001/2014 The Complete in a Silent Way Sessions

- 2001 Pangaea [3]

- 2001 Live In Stockholm, 1960 [2]

- 2001 At Newport 1958

- 2001 'round About Midnight (remastered)

- 2001 Live At The Fillmore East (march 7, 1970) It's About Thattime -

- 2001 The Essential Miles Davis

- 2000 Blue Miles

- 2000 All Stars Recordings

- 2000 Ascenseur Pour LÉchafaud

- 2000 Bluing

- 2000 Boppin The Blues

- 1999 In Person, Friday Night At The Blackhawk San Francisco, Vol. 1

- 1999 In Person, Saturday Night At The Blackhawk,san Francisco, Vol. 2

- 1999 Panthalassa: The Remixes

- 1999 Miles Davis & Sonny Stitt

- 1999 Love Songs

- 1999 Olympia 11 Octobre 1960, Part 1

- 1999 Cool Blues

- 1999 Olympia 11 Octobre 1960, Part 2

- 1999 Olympia 20 Mars 1960, Part 1

- 1999 Olympia 20 Mars 1960, Part 2

- 1998/2020 Hi-Hat All-Stars (Live)

- 1998 Ballads

- 1998 The Complete Birth of the Cool (Remastered)

- 1998 The Complete Columbia Studio Recordings (CD3)

- 1998 The Complete Birth Of The Cool

- 1998 The Complete Bitches Brew Sessions

- 1998 The Mute

- 1997 Young Miles 1945-1946 (Complete Edition Volume 1)

- 1997 At Fillmore West Black Beauty (2CD)

- 1997 Young Miles Vol.1 (1945-1946) - Masters Of Jazz

- 1997 Autumn Leaves

- 1997 Original Jazz Classics Collection

- 1996 Ballads And Blues

- 1996 Live Around The World

- 1996 Bluing: Miles Davis Plays The Blues

- 1996 Evolution Of A Genius (1957-1958)

- 1996 In A Silent Way

- 1995 Jazz & Blues Collection

- 1995 Highlights From The Plugged Nickel

- 1995 Another Bitches Brew [2]

- 1995 Evolution Of A Genius- 1945-1954

- 1995 Miles Davis & Freddie Hubbard

- 1995 Voodoo Down

- 1994 Birdland Sessions [2]

- 1994 Miles Davis Vol.2 Jean Pierre

- 1994 Essentiel Jazz. Miles Davis Vol.2 Jean Pierre

- 1993 The Blue Note And Capitol Recordings

- 1993 The Blue Note And Capitol Recordings (CD4)

- 1993 The Blue Note And Capitol Recordings (CD2)

- 1993 The Blue Note And Capitol Recordings (CD3)

- 1992 Greatest Jazz [2]

- 1992 In Stockholm 1960 Complete

- 1992 The Best Of Miles Davis - The Capitol / Blue Note Years

- 1992 First Miles

- 1991 Doo-bop

- 1991 Music For Brass

- 1991 Doo-Bop

- 1991 Circle In The Round (2CD)

- 1991 Miles Davis 1957-58

- 1991 Circle In The Round (CD1)

- 1991 Circle In The Round (CD2)

- 1991 Evolution of a Genius 1957-58

- 1991 Live at the Royal Roost 1948 / Live at Birdland 1952

- 1990 Old Devil Moon (CD1)

- 1990 Old Devil Moon (CD2)

- 1990 Old Devil Moon (CD3)

- 1990 Jazz Masters (E.F.S.A Collection)

- 1990 Evolution Of A Genius (1945-1954)

- 1990 15 Reflective Recordings

- 1990 Conception

- 1989 Aura

- 1989 Live At Montreux Jazz Festival (CD1)

- 1989 Live At Montreux Jazz Festival (CD2)

- 1989 Amandla [3]

- 1989 Evolution Of A Genius 1954-1956

- 1989 Live At Montreux Jazz Festival

- 1989 Ascenseur Pour Lechafaud

- 1989 Elevator to the Gallows

- 1988 Munich Concert (CD1)

- 1988 Munich Concert (CD2)

- 1988 Munich Concert (CD3)

- 1988 Perfect Way

- 1988 The Columbia Years 1955-1985

- 1987 Dark Magus (2CD)

- 1987 Isle Of Wight

- 1987 At Fillmore (2CD)

- 1987 Bitches Brew Columbia Jazz Masterpieces

- 1987 Chronicle: The Complete Prestige Recordings 1951–1956

- 1986 Tutu [4]

- 1985 [2000] Youre Under Arrest

- 1985 You're Under Arrest [4]

- 1985 Aura (2009 Tccac)

- 1985 Agharta (2CD)

- 1985 The Miles Davis Quintet Featuring John Coltrane: Stockholm 1960

- 1984 Decoy [2]

- 1983 Star People [2]

- 1982; 2014 We Want Miles (Expanded Edition)

- 1982 We Want Miles (2CD)

- 1981 The Man With The Horn [3]

- 1979 Jack Johnson

- 1976 Water Babies [2]

- 1975 Agharta [6]

- 1975 Pangaea

- 1974 Dark Magus: Live At Carnegie Hall - Cd 2

- 1974 Dark Magus: Live At Carnegie Hall - Cd 1

- 1974 Big Fun [7]

- 1974 Get Up With It [4]

- 1974 Big Fun, Part 1

- 1974 Big Fun, Part 2

- 1973 In Concert. Live At Philharmonic Hall, New York

- 1973 Black Beauty (Miles Davis At Fillmore West)

- 1972 In Concert-live At Philharmonic Hall (2CD)

- 1972 On The Corner [5]

- 1971 Live-Evil [7]

- 1971 What I Say (2CD) [1994, remaster]

- 1971 A Tribute To Jack Johnson [5]

- 1971 Another Bitches Brew (2CD)

- 1970 / 2010 Bitches Brew (40th Anniversary Edition)

- 1970 Directions (cd1)

- 1970 Directions (cd2)

- 1970 A Tribute To Jack Johnson (2009 TCCAC)

- 1970 Bitches Brew [8]

- 1970 At Fillmore: Live At The Fillmore East (2CD)

- 1970 Bitches Brew (1970) {columbia, Gp 26, Lp, Original Canadian Pressing}

- 1970 Black Beauty: Miles Davis At Fillmore West (CD1)

- 1970 Black Beauty: Miles Davis At Fillmore West (CD2)

- 1970 The Cellar Door Sessions 1970 (CD6)

- 1970 The Cellar Door Sessions 1970 (CD5)

- 1970 The Cellar Door Sessions 1970 (CD3)

- 1970 The Cellar Door Sessions 1970 (CD4)

- 1970 Bitches Brew Live (2011 Remaster)

- 1970 Black Beauty - Miles Davis At Fillmore West [2]

- 1970 Live - Evil

- 1970 Live-Evil [3]

- 1970 The Cellar Door Sessions 1970 (CD2)

- 1970 The Cellar Door Sessions 1970 (CD1)

- 1969 Bitches Brew (CD1)

- 1969 Bitches Brew (CD2)

- 1969 Bitches Brew (Sony Mastersound 2006, CD1)

- 1969 Bitches Brew (Sony Mastersound 2006)(CD2)

- 1969 Miles Festiva De Juan Pins

- 1969 Big Fun (CD1)

- 1969 Untitled

- 1969 The Complete In A Silent Way Sessions CD3

- 1969 The Complete In A Silent Way Sessions CD2

- 1969 The Complete In A Silent Way Sessions CD1

- 1969 In a Silent Way (MFSL 2012)

- 1969 In A Silent Way [8]

- 1969 Filles De Kilimanjaro (2002 Remaster)

- 1968 Filles De Kilimanjaro [6]

- 1968 Miles In The Sky [7]

- 1968 Nefertiti [6]

- 1968 Filles De Kilimanjaro (1990 Remastered)

- 1968 The Complete In A Silent Way Sessions (3CD)

- 1967 Nefertiti [2]

- 1967 Sorcerer [5]

- 1967 Antwerp Blues

- 1967 Miles Smiles [2]

- 1966 Miles Smiles

- 1966 Four & More

- 1965 E.S.P. [5]

- 1965 At Plugged Nickel, Chicago (2CD)

- 1965 E.s.p.

- 1964 Quiet Nights

- 1964 Miles In Berlin [2]

- 1964 'four' & More

- 1964 My Funny Valentine: Miles Davis In Concert [3]

- 1964 Miles In Tokyo

- 1964 Live In Sindelfingen

- 1963/2023 Seven Steps To Heaven (2023 Remaster)

- 1963 Miles Davis In Europe [2]

- 1963 Seven Steps To Heaven [5]

- 1963 Miles Davis In Europe {2007 Sony Music SICP-1210 Japan}

- 1963 Cote Blues

- 1963 Quiet Nights [2]

- 1963 Miles in Antibes

- 1962 Mode Study

- 1961/2011 In Person, Friday Nights At The Blackhawk, San Francisco, Vol.I

- 1961/2011 In Person, Friday Nights At The Blackhawk, San Francisco, Vol.II

- 1961 Steamin' With The Miles Davis Quintet [Hi-Res]

- 1961 Someday My Prince Will Come [12]

- 1961 Someday My Prince Will Come

- 1961 Someday My Prince Will Come

- 1961 Someday My Prince Will Come

- 1961 Someday My Prince Will Come

- 1961 Someday My Prince Will Come

- 1961 Someday My Prince Will Come

- 1961 Someday My Prince Will Come

- 1961 Someday My Prince Will Come

- 1961 Someday My Prince Will Come

- 1961 Someday My Prince Will Come

- 1961 Someday My Prince Will Come

- 1961 Someday My Prince Will Come

- 1961 Miles Davis At Carnegie Hall

- 1961 In Person At The Blackhawk Saturday Night (2003 Remastered)(2CD)

- 1961 More Music From The Legendary Carnegie Hall Concert

- 1961 At The Blackhawk - Vol. 2

- 1961 Someday My Prince Will Come (2010) [Hi-Res stereo] 24bit 88kHz

- 1961 Steamin' With The Miles Davis Quintet (2016) [Hi-Res stereo] 24bit 192kHz

- 1961 In Person, Saturday Night At The Blackhawk, San Francisco Volume 1,2

- 1960 Sketches Of Spain [7]

- 1960 Manchester Concert (2CD)

- 1960 Olympia, 20.03.1960

- 1959/2015 Miles Davis and the Modern Jazz Giants (Bonus Track Version)

- 1959 Kind Of Blue [10]

- 1959 Porgy And Bess [4]

- 1959 Workin' With The Miles Davis Quintet

- 1959 1958 Miles [2]

- 1959 Kind Of Blue: 50th Anniversary (2CD)

- 1959 Another Tracks Of Kind Of Blue

- 1959 Workin' With The Miles Davis Quintet (2016) [Hi-Res stereo] 24bit 192kHz

- 1958/2019 Jazz Track (Complete Edition, Bonus Track Version)

- 1958 Porgy And Bess [3]

- 1958 Ascenseur Pour L'echafaud [3]

- 1958 Milestone (MFSL 2012)

- 1958 Miles Davis And The Modern Jazz Giants & Somethin' Else [2]

- 1958 Miles & Selections From Porgy And Bess

- 1958 Milestones [5]

- 1958 1958 Miles & Selections From Porgy And Bess [remaster]

- 1958 '58 Sessions Featuring Stella By Starlight

- 1958 '58 Sessions Featuring Stella By Starlightz

- 1958 Porgy & Bess

- 1958 Ballads & Blues

- 1958 Jazz At The Plaza, Vol. I

- 1958 Relaxin With The Miles Davis Quintet

- 1958 Relaxin' With The Miles Davis Quintet

- 1958 Milestones.....

- 1957/2021 Ascenseur Por L´Echafaud (Bonus Track Version)

- 1957/2021 Round About Midnight (Bonus Track Version)

- 1957 [2001] ‘Round About Midnight

- 1957 Cookin' With The Miles Davis Quintet

- 1957 Relaxing & Bag's Groove [2]

- 1957 Round About Midnight & Miles Ahead [2]

- 1957 Cookin' & Milestones [2]

- 1957 Miles Ahead [3]

- 1957 Bags Groove [10]

- 1957 Bags' Groove (Japanese Edition 2007)

- 1957 'Round About Midnight

- 1957 Round About Midnight

- 1957 Ascenseur Pour L'Echafaud (Lift To The Scaffold)

- 1956 Steamin' With The Miles Davis Quintet [2]

- 1956 'Round About Midnight (Legacy Edition)(CD1)

- 1956 'Round About Midnight ( Legacy Edition)(CD2)

- 1956 'Round About Midnight

- 1956 Miles Davis And The Modern Jazz Giants

- 1956 The New Miles Davis Quintet & Miles Davis With Horns

- 1956 Volume 2 (Blue Note 75th Anniversary)

- 1956 Volume 1 (Blue Note 75th Anniversary)

- 1956 Quintet / Sextet (1997 DCC Remastered)

- 1956 Workin' With The Miles Davis Quintet

- 1956 Dig

- 1956 Relaxin' With The Miles Davis Quintet

- 1956 Miles - The New Miles Davis Quintet (2016, Hdtracks)

- 1956 Relaxin' With The Miles Davis Quintet (2004) [Hi-Res stereo] 24bit 192kHz

- 1956 Miles Davis And Horns

- 1956 Relaxin’ With The Miles Davis Quintet

- 1955 Blue Moods [2]

- 1955 The Musings Of Miles [2]

- 1955 Blue Moods & Quintet/sextet

- 1955 Miles Davis / Quintete/ Sextet

- 1955 Miles: The New Miles Davis Quintet (Remastered RVG 2009)

- 1955 Miles Davis Volume 2

- 1955 The New Miles Davis Quintet

- 1955 Quintete / Sextet

- 1954 Bags' Groove

- 1954 Vol. 3

- 1954 Volume 2 (2013 Remaster) (24bit 192kHz, Stereo)

- 1953 Miles Davis And Horns

- 1953 Volume 2

- 1953 Vol. 2 [2]

- 1952 Volume One

- 1952 Volume 1 (2013 Remaster) (24bit 192kHz, Stereo)

- 1950 Birth Of The Cool & Conception

- 1949 Birth Of The Cool [2]

Bootleg

- 2009 Live In Vienna 1973

- 2005 Amsterdam Concert

- 1995 The Last Bebop Session: Live at Birdland, June 30, 1950

- 1991 1991-07-23, Stadio Olimpico, Rome, Italy

- 1988 1988-07-10, Philharmonie Am Gasteig, Munich, Germany - 2496

- 1987 1987-10-27, Sardine's, Oslo, Norway - 161'33b

- 1986 1986-08-31 Detroit, MI

- 1986 1986-11-17, Wembley Conference Centre, London, UK

- 1985 1985-08-17, Pier 84, New York, NY

- 1985 1985-04-23, Rainbow Music Hall, Denver, CO

- 1983 1983-06-26, Avery Fisher Hall, New York, NY - Late Show

- 1983 1983-01-29, Rainbow Music Hall, Denver, CO (Early Set) 99'32

- 1983 1983-01-29, Rainbow Music Hall, Denver, CO (Late Set) 99'50

- 1983 1983-04-13, Chapiteau Porte de Pantin, Paris, France

- 1983 1983-04-25, Koninklijk Circus, Brussel, Belgium

- 1983 1983-05-25, Festival Hall, Osaka, Japan

- 1983 1983-05-20, Sendai, Miyagi, Japan 88'25

- 1982 1982-04-26, Teatro Tenda Pianeta, Rome, Italy

- 1982 1982-11-17, Yale University, New Haven, CT - 101'10a

- 1982 1982-08-03, Greek Theatre, Los Angeles, CA

- 1982 1982-12-31, Felt Forum, New York, NY

- 1982 1982-08-03, Greek Theatre, Los Angeles, CA [Rec4 d] partial

- 1973 1973-04-05, Paramount Theatre, Seattle, WA

- 1971 1971-11-13, Royal Festival Hall, London, England

- 1970 1970-XX-XX, Petersburg, NJ - 110.17

- 1970 Miles at The Fillmore: Miles Davis 1970: The Bootleg Series, Vol. 3

- 1969 Live In Europe 1969: The Bootleg Series Vol 2 3CD

- 1969 1969-06-21, Blue Coronet Club, New York, NY

- 1969 1969-06-29, Blue Coronet Club, New York, NY

- 1966 1966-05-21, Oriental Theatre, Portland, OR

- 1964 Miles In Tokyo 7-12-1964

- 1964 Miles In Kyoto 7-15-1964

- 1960 Pars Jazz Concert - Olympia, 20.03.60

- 1960 1960-09-27, Free Trade Hall, Manchester, England (Late Show)

- 1957 1957-02-23, Peacock Alley Lounge, St. Louis, MO

- 1955 1955-02-XX, The Hi-Hat, Boston, MA

- 1947 1947-11-XX, Argyle Show Lounge, Chicago, IL

Compilation

- 2023 Music around the World by Miles Davis

- 2023 MILES DAVIS INTEGRAL 1957-1962

- 2023 The Classic Albums Collection

- 2020 Playlist: Hi-Res Masters

- 2019 The Complete Birth Of The Cool

- 2018 The Best Of

- 2015 The Last Word - The Warner Bros. Years

- 2015 At Newport 1955-1975 (The Bootleg Series Vol. 4)

- 2014 Take Off: The Complete Blue Note Albums

- 2011 Bitches Brew Live

- 2010 Original Album Classics

- 2009 Greatest Hits

- 2007 BD Music & Cabu Present: Miles Davis

- 2003 The Complete Jack Johnson Sessions

- 2002 The Complete Miles Davis At Montreux: 1973-1991

- 2002 The Complete Miles Davis At Montreux 1973-1991 [2]

- 2001 Young Miles (4CD)

- 2001 Super Hits

- 2000 Ken Burns Jazz: The Definitive Miles Davis

- 1999 Young Miles Vol.1 (1945-1946)

- 1996 This Is Jazz 8: Miles Davis Acoustic

- 1988 First Miles (2003 Remastered)

- 1988 Miles Davis Volume One

- 1988 Miles Davis: The Columbia Years 1955-1985

- 1981 Directions (1997 Japan Reissue, Remastered) (2CD)

- 1979 Circle In The Round (1997 Japan Reissue, Remastered) (2CD)

- 1965 Complete Live At Plugged Nickel 1965

- 1960 Jazz Collection CD2: Miles Davis

- 1958 1958 Miles

- 1957 Birth of the Cool

- 1957 Walkin'

- 1957 Birth Of The Cool [2]

- 1957 Bags Groove

- 1956 Miles Davis, Volume 1

- 1956 Miles Davis, Volume 2

- 1956 Blue Haze [2]

- 1956 Miles Davis and Horns

- 1956 Dig

- 1954 Workin' With the Miles Davis Quintet / The Musings of Miles

- 1954 Blue Haze

EP

Live album

- 2021 Merci Miles! Live At Vienne

- 2018 Live In Boston 1972

- 2014 Live At The Fillmore East (march 7, 1970). It's About That Time (2CD)

- 2005 Miles Davis Quintet with John Coltrane: Live in Zurich

- 1999 Olympia 11 Juillet 1973

- 1997 Fat Time

- 1996 Live Around The World (Reissue, Remastered 2002)

- 1995 Another Bitches Brew - Two Concerts In Belgrade

- 1993 Miles & Quincy Live At Montreux

- 1987 Live Miles: More Music From the Legendary Carnegie Hall Concert

- 1983 Live In Poland (CD1) (Unofficial Release )

- 1983 Live In Poland (CD2) (Unofficial Release )

- 1983 What It Is: Montreal - Live at Theatre St-Denis, Canada - July 7, 1983

- 1982 We Want Miles

- 1981 We Want Miles (2CD)

- 1981 Live At The Hollywood Bowl [2]

- 1977 In Paris Festival International deJazz May, 1949

- 1977 Dark Magus [2]

- 1976 Miles Davis at Plugged Nickel, Chicago

- 1976 Miles Davis At Plugged Nickel, Chicago

- 1973 In Concert: Live at Philharmonic Hall (2CD)

- 1973 Jazz at the Plaza Vol. I [2]

- 1973 In Concert

- 1970 Live At The Fillmore East (March 7, 1970). It's About That Time

- 1970 Black Beauty: Miles Davis At Fillmore West [3]

- 1969 Miles in Tokyo: Miles Davis Live in Concert [2]

- 1969 Bitches Brew Live

- 1969 Miles In Tokyo

- 1966 'Four' & More - Recorded Live In Concert [3]

- 1965 Miles in Berlin

- 1965 My Funny Valentine: Miles Davis in Concert

- 1965 My Funny Valentine - Miles Davis In Concert [2]

- 1964 Miles Davis in Europe

- 1963 Live at the 1963 Monterey Jazz Festival

- 1962 Miles Davis at Carnegie Hall [3]

- 1961 In Person, Friday Night At The Blackhawk, San Francisco Vol. 1 [2]

- 1961 In Person, Friday Night At The Blackhawk, San Francisco Vol. 2 [2]

- 1961 Miles Davis at Carnegie Hall

- 1961 At The Blackhawk - Vol. 1

- 1960 Live At The Olympia

- 1957 Quintet in Concert Live at the Olympia, Paris, November 30 - 1957

- 1950 The Last Bebop Session - Live At Birdland, June 30, 1950

Single

Soundtrack

- 2016 Miles Ahead (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack)

- 1971 Jack Johnson [2]

- 1957 Ascenseur Pour L'Échafaud

- 1957 Ascenseur Pour L'echafaud

- 1957 Ascenseur Pour L'Echafaud [2]