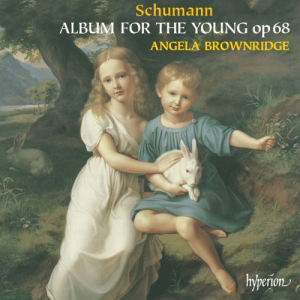

Angela Brownridge - Schumann: Album for the Young '2000

| Artist | Angela Brownridge Related artists |

| Album name | Schumann: Album for the Young |

| Country | |

| Date | 2000 |

| Genre | Classical Piano |

| Play time | 01:11:38 |

| Format / Bitrate | Stereo 1420 Kbps

/ 44.1 kHz MP3 320 Kbps |

| Media | CD |

| Size | 195 mb |

| Price | Download $1.95 |

Order this album and it will be available for purchase and further download within 12 hours

Pre-order album Tracks list

Tracks list

Tracklist 01. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 1, Melodie 02. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 2, Soldatenmarsch 03. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 3, Trällerliedchen 04. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 4, Ein Choral 05. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 5, Stückchen 06. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 6, Armes Waisenkind 07. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 7, Jägerliedchen 08. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 8, Wilder Reiter 09. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 9, Volksliedchen 10. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 10, Fröhlicher Landmann, von der Arbeit zurückkehrend 11. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 11, Sizilianisch 12. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 12, Knecht Ruprecht 13. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 13, Mai, lieber Mai 14. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 14, Kleine Studie 15. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 15, Frühlingsgesang 16. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 16, Erster Verlust 17. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 17, Kleiner Morgenwanderer 18. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 18, Schnitterliedchen 19. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 19, Kleine Romanze 20. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 20, Ländliches Lied 21. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 21 in C Major 22. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 22, Rundgesang 23. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 23, Reiterstück 24. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 24, Ernteliedchen 25. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 25, Nachklänge aus dem Theater 26. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 26 in F Major 27. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 27, Kanonisches Liedchen 28. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 28, Erinnerung 29. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 29, Fremder Mann 30. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 30 in F Minor 31. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 31, Kriegslied 32. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 32, Sheherazade 33. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 33, Weinlesezeit – Fröhliche Zeit! 34. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 34, Thema 35. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 35, Mignon 36. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 36, Lied italienischer Marinari 37. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 37, Matrosenlied 38. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 38, Winterzeit I 39. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 39, Winterzeit II 40. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 40, Kleine Fuge 41. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 41, Nordisches Lied 42. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 42, Figurierter Choral 43. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68: No. 43, Silvesterlied Though Bach, Mozart and others had written music for young and inexpert performers, Schumann was the first great composer to penetrate imaginatively into the world of children. The earliest of his works to evoke childhood was Kinderszenen (‘Scenes of Childhood’) of 1838, whose tender portraits of a carefree innocence are intimately bound up with his longing for Clara Wieck. But, though technically undemanding, the Kinderszenen are essentially adults’ music, in Schumann’s words ‘reminiscences of a grown-up for grown-ups’. Ten years later, now married to Clara and with three daughters, Schumann composed his Album for the Young, a collection of forty-three miniatures written specifically for children. The first pieces were intended as a birthday present for his eldest daughter, Marie, who was seven on 1 September 1848; then, as Schumann wrote to a friend, ‘one after another was added’, with a gradual increase in difficulty. As an entry in Clara’s family diary reveals, Schumann was encouraged to produce an extended collection of pieces for children by the thought that most of the music learned in piano lessons was worthless; and his didactic purpose is underlined by his original intention of supplementing the pieces with extracts from other composers’ works, and by the list of musical maxims (Musikalische Haus- und Lebensregeln) which he added to the second, 1851, edition of the Album. These include such pungently worded precepts as ‘Don’t just tinkle at the keys!’ and ‘Play rhythmically! Many virtuosi sound like a drunkard walking! Don’t imitate them!’ The Album falls into two parts, with the first eighteen pieces designed for young children and the later numbers for ‘more grown-up’ players. But even in the last pieces Schumann shields his pianists from the more difficult keys: nowhere does he venture beyond three flats or four sharps. Perhaps surprisingly, all the pieces are in duple (2/4 and 4/4) or compound duple (6/8) time. But Schumann creates a wealth of rhythmic diversity within his self-imposed limitations, and monotony only creeps in when all the pieces are dutifully played one after the other—a notion which would surely have horrified the composer. It is only to be expected that the first, and simplest, pieces, written expressly for Marie, should contain little of the poetry found in many of the later ones. Each is designed to highlight a particular technical point—legato and staccato playing, dotted rhythms and so on. But Schumann’s love of cryptic allusions could well lie behind the very opening of the first piece, whose descending five-note scale had come to assume a special significance in his work, closely associated with his love for Clara. A different kind of allusion occurs in SoldatenÂmarsch (‘Soldiers’ March’), whose initial bars recreate in duple time the beginning of the Scherzo in Beethoven’s ‘Spring’ Sonata for violin and piano. The fourth piece, Ein Choral, designed to develop a smooth legato, is a simple harmonizaÂtion of the chorale ‘Rejoice O my soul’ used by Bach and others; Schumann is to treat the same melody much more elaborately in No 42, Figurierter Choral. A more lively note is introduced with the ‘Little Hunting Song’ (Jägerliedchen, No 7), with its buoyant 6/8 metre and crisp staccato writing, while the following number, Wilder Reiter (‘The Wild Rider’), in similar metre, is the first to entrust part of the melodic line to the left hand. One of the most touching of the early numbers is ‘Little Folksong’ (Volksliedchen, No 9), which contrasts mournful D minor music with a dance-like centrepiece in D major. Here Schumann is already demanding sharp emotional responses from his young players. A similar acute characterization is needed for No 12 (Knecht Ruprecht), with its eerie unisons in the depths of the keyboard and adventurously modulating central episode. (The ‘Knecht Ruprecht’ of the title is, in German folklore, the mischievous helper of Santa Claus.) In complete contrast are the two delightful numbers which evoke spring: No 13, Mai, lieber Mai, the first of several pieces in the Album to suggest Mendelssohn’s Songs without Words, and the more inward-looking and chromatic No 15, FrühlingsÂgesang, where the soft pedal is used to deepen the music’s rapt contemplation. The second part of the Album opens with ‘Little Romance’ (Kleine Romanze), whose melodic shape, texture and faint sense of agitation again call to mind Mendelssohn. Several of the more boisterous numbers in Part Two carry descriptive titles similar to those in the first part, though the music is now more intricately worked. Especially characterful are ‘The HorseÂman’ (Reiterstück, No 23) with its magical coda fading into the distance; ‘Echoes of the Theatre’ (Nachklänge aus dem Theater, No 25), which imitates various sounds of the orchestra; and No 36, Lied italienischer Marinari (‘Italian Sailor’s Song’), with its fiery tarantella rhythms. But Schumann dispenses with picturesque childlike rides for the more reflective numbers which predominate in the second part of the Album. These include two numbers with literary associÂations (Sheherazade and Mignon, with their exquisite veiled sonorities) and two in which Schumann pays tribute to fellow composers: No 28, Erinnerung—‘Remembrance’ (with its allusion, quite possibly intentional, to the song ‘Dein Bildnis wunderselig’ from the Op 39 Liederkreis), which is dedicated to the memory of Mendelssohn, who had died in November 1847; and Nordisches Lied (‘Northern Song’, No 41), subÂtitled ‘Greetings to Niels Gade’ in which the first four notes G-A-D-E represent the Danish composer’s name. Among those pieces which bear no extra-musical desÂcription, the three untitled numbers (21, 26 and 30) are in Schumann’s most intimate lyrical vein. Another Beethoven allusion, this time to the trio ‘Euch werde Lohn’ from Fidelio, occurs in the searching, harmonically subtle No 21. Even finer is No 30, with its rich textures and yearning chromaticism. Schumann also includes three pieces designed to introduce the player to various types of counterpoint. No 27 is a canon at the octave, led first by the right, then by the left hand, while No 40, Kleine Fuge, takes the form of a moto perpetuo prelude followed by a fugue whose puckish 6/8 subject is a transformation of the prelude’s opening phrase. The final contrapuntal number is the Figurierter Choral, No 42, in which the melody first heard in No 4 is enriched with flowing counter-melodies. But it is characteristic of the Album that these contrapuntal pieces should contain nothing of dry pedantry. As in the whole collection, Schumann’s didactic purpose is balanced by the freshness of his poetic imagination and the extraordinary sympathy and understanding he shows for the mind of a child.

Angela Brownridge

Album

- 2024 Angela Brownridge plays Tchaikovsky & Schumann

- 2020 Satie: Jack-in-the-Box & Other Piano Favourites

- 2019 Tchaikovsky: The Seasons and Piano Sonata in G

- 2017 Chopin: The Four Ballades & Piano Sonata No. 2

- 2017 Debussy: Preludes, Book 1 & 2

- 2005 Kenneth Leighton: Complete Solo Piano Works

- 2000 Schumann: Album for the Young

- 1999 Gershwin: Fascinating Rhythm - The Complete Music for Solo Piano

- 1989 Tchaikovsky: 18 Piano Pieces, Op. 72