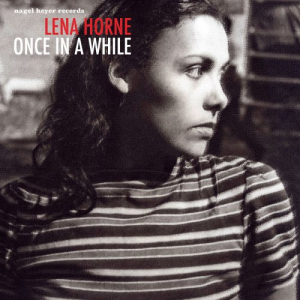

Lena Horne - Once in a While '2018

| Artist | Lena Horne Related artists |

| Album name | Once in a While |

| Country | |

| Date | 2018 |

| Genre | Vocal Jazz |

| Play time | 01:51:20 |

| Format / Bitrate | Stereo 1420 Kbps

/ 44.1 kHz MP3 320 Kbps |

| Media | CD |

| Size | 266 / 521 mb |

| Price | Download $4.95 |

Order this album and it will be available for purchase and further download within 12 hours

Pre-order album Tracks list

Tracks list

Tracklist --------- 01. I Got Rhythm 02. Baby, Wont You Please Come Home 03. Summertime 04. I Let a Song Go out of My Heart 05. Im Beginning to See the Light 06. I Aint Got Nobody 07. A Ride on a Rainbow / Never Never Land / I Said No / Some People 08. Im Confessin (That I Love You) 09. You Dont Have to Know the Language 10. Honeysuckle Rose 11. Ive Found a New Baby 12. I Understand 13. Out of My Continental Mind 14. I Get the Blues When It Rains 15. Hows Your Romance / After You / Love of My Life / Its All Right with Me 16. I Love to Love 17. Ive Grown Accustomed to His Face 18. Mood Indigo 19. Maybe 20. I Surrender, Dear 21. Dont Commit the Crime 22. Today I Love Evrybody 23. Just One of Those Things 24. I Only Have Eyes for You 25. Stormy Weather 26. Tomorrow Mountain 27. Get Rid of Monday 28. The Man I Love 29. How Do You Say It 30. I Wonder What Became of Me 31. Let Me Love You 32. I Concentrate on You 33. Mad About the Boy Singer/actress Lena Hornes primary occupation was nightclub entertaining, a profession she pursued successfully around the world for more than 60 years, from the 1930s to the 1990s. In conjunction with her club work, she also maintained a recording career that stretched from 1936 to 2000 and brought her three Grammys, including a Lifetime Achievement Award in 1989; she appeared in 16 feature films and several shorts between 1938 and 1978; she performed occasionally on Broadway, including in her own Tony-winning one-woman show, Lena Horne: The Lady and Her Music, in 1981-1982; and she sang and acted on radio and television. Adding to the challenge of maintaining such a career was her position as an African-American facing discrimination personally and in her profession during a period of enormous social change in the U.S. Her first job in the 1930s was at the Cotton Club, where blacks could perform but not be admitted as customers; by 1969, when she acted in the film Death of a Gunfighter, her characters marriage to a white man went unremarked in the script. Horne herself was a pivotal figure in the changing attitudes about race in the 20th century; her middle-class upbringing and musical training predisposed her to the popular music of her day, rather than the blues and jazz genres more commonly associated with African-Americans, and her photogenic looks were sufficiently close to Caucasian that frequently she was encouraged to try to pass for white, something she consistently refused to do. But her position in the middle of a social struggle enabled her to become a leader in that struggle, speaking out in favor of racial integration and raising money for civil rights causes. By the end of the century, she could look back at a life that was never short on conflict, but that could be seen ultimately as a triumph. Lena Mary Calhoun Horne was born June 30, 1917, in the New York City borough of Brooklyn. Both sides of her family claimed a mixture of African-Americans, Native Americans, and Caucasians, and both were part of what black leader W.E.B. DuBois called the talented tenth, the upper stratum of the American black population made up of middle-class, well-educated African-Americans. Her parents, however, might both be described as mavericks from that tradition. Her father, Edwin Fletcher Horne, Jr., worked for the New York State Department of Labor, but one of her biographers describes him more accurately as a numbers banker: his real profession was gambling. Her mother, Edna Louise (Scottron) Horne, aspired to act. The two lived in a Brooklyn brownstone with Hornes paternal grandparents, teacher and newspaper editor Edwin Fletcher Horne, Sr. and his wife, Cora (Calhoun) Horne, a civil rights activist and early member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which had been founded in 1909 and was headed by DuBois. (Indeed, Horne herself could claim a similar association. A photograph of her as a two-year-old appears on the cover of the October 1919 issue of the NAACPs Branch Bulletin, describing her as the organizations youngest member!) Hornes father and mother separated in August 1920 when she was three, later divorcing. Her father moved to Seattle before eventually settling in Pittsburgh, where he ran a hotel when he wasnt traveling the country to attend and gamble on sporting events. Horne and her mother initially remained in her grandparents home, but when Horne was about five, her mother left to pursue her acting career, initially with the Lafayette Stock Company in Harlem. Horne recalled in her 1965 autobiography Lena (written with Richard Schickel) that she visited her mother occasionally and even made her stage debut as a young child in the play Madame X in Philadelphia. After a couple of years, Hornes mother took her on the road with her, and from the age of six or seven to the age of 11 she was raised in various locations in the South and the Midwest by her mother, relatives, and paid companions, with frequent trips back to Brooklyn. Finally, in early 1929, she returned permanently to her grandparents home. She stayed there until September 1932, when her grandmother died, then went to live with a family friend. While attending Girls High School in Brooklyn, she also took dancing lessons, even playing with a group at the Harlem Opera House for a week in 1933. Her mother, meanwhile, had been living in Cuba, where she had remarried. She returned to New York and reclaimed her daughter. They lived in Brooklyn, then moved to the Bronx, and eventually Harlem. Money was tight in those Depression years, and Hornes mother obtained an audition for her at the Cotton Club through a friend. She was hired as a chorus girl at the club at the age of 16. Horne first attracted attention beyond the chorus when she replaced a sick performer in a performance of Harold Arlen and Ted Koehlers As Long As I Live with Avon Long. Soon after, she sang Cocktails for Two with Claude Hopkins & His Orchestra on a theater date with the Cotton Club troupe, and she began taking singing lessons. She was spotted at the Cotton Club by a theatrical producer and cast in a small part in the play Dance with Your Gods, which opened a brief run on October 6, 1934, marking her Broadway debut. In 1935, she left the Cotton Club and took a job singing with Noble Sissle & His Orchestra, billed as Helena Horne. She made her recording debut with Sissle on March 11, 1936, singing Thats What Love Did to Me and I Take to You, both released by Decca Records. Horne was introduced to Louis Jordan Jones, a Pittsburgh political operative, by her father. In January 1937, she retired from show business to marry him; their daughter, Gail, was born December 21, 1937. Jones owed his job as a clerk in the county coroners office to political patronage. It did not bring in much money, and in 1938, when Horne was approached by an agent with an offer to co-star in a low-budget all-black movie musical with a mere ten-day shooting schedule in Hollywood, she accepted. The film was The Duke Is Tops, released in July 1938. Later in the year, Horne was asked to take on a more time-consuming project, a part in a new mounting of producer Lew Leslies all-black musical revue Blackbirds. Again, she accepted in the name of increasing the family income, spending months in rehearsals and out-of-town tryouts before Lew Leslies Blackbirds of 1939 opened on Broadway on February 11, 1939. One of Hornes numbers was Youre So Indifferent, written by Sammy Fain and Mitchell Parish, a song she would keep in her repertoire. The show ran only nine performances, closing February 18. Horne returned to Pittsburgh, where she temporarily separated from her husband, then reconciled with him. She began taking singing engagements in the homes of wealthy families in the area. She also became pregnant again, and her son, Edwin Fletcher (Teddy) Jones, was born in February 1940. That fall, she made a final separation from her husband (they were formally divorced in June 1944) and moved to New York to restart her career. In December, she accepted an offer to join the orchestra of white bandleader Charlie Barnet, one of the few instances of integration among swing bands at the time. She made a handful of recordings with Barnet in January 1941 that were released on RCA Victors discount label Bluebird Records. After only a few months, however, the difficulties of encountering racial discrimination while touring and her desire to have a home where she could raise her children (Jones let her have her daughter, but ultimately retained custody of her son) caused her to look for a job in New York, and in March 1941 she began singing at the prestigious nightclub Café Society Downtown in Greenwich Village, again billed as Helena Horne. She also did radio work, becoming a regular on the Chamber Music Society of Lower Basin Street series broadcast by NBC. In June 1941, she was the featured vocalist on a series of recordings made by Henry Levine & the Dixieland Jazz Group of the show for RCA, cutting a selection of W.C. Handy tunes for a 78-rpm album called The Birth of the Blues. She also sang on recordings by Artie Shaw and Teddy Wilson (who was her accompanist at Café Society). Horne left her New York engagement after six months when she received an offer to help open a club in Los Angeles. She arrived on the West Coast in September 1941 to find that the club was not yet ready to open; after Pearl Harbor led to American involvement in World War II and a shortage of building materials, it would not be any time soon. In the meantime, she was contracted directly to RCA and in December 1941 cut eight songs backed by an orchestra conducted by Lou Bring for her first solo album, Moanin Low. Among its selections were songs she would sing throughout her career, including a revival of the 1933 Cotton Club song Stormy Weather, written by Harold Arlen and Ted Koehler, and George and Ira Gershwins 1928 standard The Man I Love. Giving up on the large club he had in mind (which was to have been called the Trocadero), Hornes sponsor instead opened a small club, the Little Troc, in February 1942 with her as headliner. She attracted attention immediately, notably from the film community, and entertained offers from the film studios before settling on MGM. Even then, she brought in a representative of the NAACP to consult on her contract so that she would not be forced to play the kind of demeaning roles usually given to African-Americans. As it turned out, however, MGM had very little else for her to play, and in all but two of the 13 features in which she would appear over the next 14 years, she would only sing a song or two, not actually have a speaking part. (The material was gathered together for audio release in 1996 by Turner/Rhino on the CD Lena Horne at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer: Aint It the Truth.) The first of these specialty appearances came right away; by May 1942 she was at work prerecording songs for a film adaptation of the Cole Porter musical Panama Hattie, one of which was the standard Just One of Those Things. At the same time, however, she continued her nightclub work, moving from the Little Troc to the Mocambo. Horne was not credited in Panama Hattie, and with the films Latin American setting, MGM may have been hoping to pass her off as Hispanic rather than Negro. But her next film would dispel any such notion; it was a treatment of the all-black musical Cabin in the Sky, with Horne not only singing but acting opposite Ethel Waters and Eddie Rochester Anderson. She shot the film in the late summer of 1942, then returned to New York where she was booked into the Café Lounge of the Savoy-Plaza Hotel starting on November 26. The engagement attracted national attention, with write-ups in magazines like Time and Life, increasing her emerging stardom. By March 1943, she was back in Hollywood for what would be her busiest time of filmmaking. MGM loaned her to 20th Century-Fox for another all-black musical, a fictionalized film biography of dancer Bill Bojangles Robinson called Stormy Weather, in which she co-starred with Robinson himself and again sang the title song, which became her signature tune. The opening of Cabin in the Sky in April found her on the road making appearances in black theaters like Washington, D.C.s Howard and Harlems Apollo. Then it was back to Hollywood, where MGM quickly began shooting musical sequences with her for one film after another: Swing Fever (an interpolation of Youre So Indifferent), Thousands Cheer (Fats Waller and Andy Razafs 1929 song Honeysuckle Rose), I Dood It (Jericho), and Broadway Rhythm (the 1924 Gershwin standard Somebody Loves Me). (Her scenes were usually excised from the prints of the films shown in the South to avoid offending racist white audiences.) Meanwhile, Stormy Weather opened, and with I Dood It and Thousands Cheer out before the end of the year, Broadway Rhythm and Swing Fever following in early 1944, and Two Girls and a Sailor (in which she sang the Mills Brothers hit Paper Doll) out in April, Horne had appearances in seven major movie musicals released in little more than a year. She would never be so active in film again. In fact, she would appear in only seven more films over the rest of her career. When her film work eased up, however, Horne had other activities to keep her busy. She entertained troops at military bases; she appeared on radio, notably the African-American-oriented military show Jubilee and the drama Suspense; she continued to do club and theater dates; and with the lifting of the musicians union recording ban that had been imposed in 1942, she was even able to make a few recordings in November 1944, backed by Horace Henderson & His Orchestra, among them her old standby As Long as I Live. (In 2002, Bluebird reissued these tracks and earlier ones on a CD called The Young Star, along with a few tracks said to have been recorded in January 1944, at a time when the ban was still in force.) Back at MGM, her only work was for the anthology film Ziegfeld Follies, in which she sang and performed Ralph Blane and Hugh Martins newly written song Love. The film, long in gestation, did not come out until January 1946. By then, Horne was working on Till the Clouds Roll By, a film biography of songwriter Jerome Kern, recording and filming a sequence that found her on-stage in Show Boat in the role of Julie LaVerne, the light-skinned Negro attempting to pass for white who sings Cant Help Lovin Dat Man and Bill. (Hornes performance of Bill was cut from the film but released on Lena Horne at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer: Aint It the Truth.) Horne parted ways with RCA in 1946 and signed to the tiny Black & White Records label, for which she recorded that fall. But when Till the Clouds Roll By opened in November, MGM took the opportunity to launch its own record label and release the first original motion picture soundtrack album; featuring Judy Garland, June Allyson, and Tony Martin, along with Horne, the Till the Clouds Roll By soundtrack reached number three in the spring of 1947, and MGM Records became Hornes new label. Meanwhile, again free of studio responsibilities, she traveled to England to perform at the London Casino that spring. She returned to Europe in October 1947 for a lengthier stay that found her performing in England, France, and Belgium. The European trip also had another purpose; she had become involved in a serious relationship with MGM arranger/conductor Lennie Hayton, but since Hayton was white, the two could not marry in California, where mixed-race marriages were illegal. Instead, they married in Paris in December 1947, and even then kept the marriage secret for two and a half years. As usual, Horne had only one film to work on in 1948, and that was Words and Music, a film biography of songwriters Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart in which she performed Where or When and The Lady Is a Tramp. Opening in December, the film generated a soundtrack album featuring Garland, Allyson, and Mickey Rooney in addition to Horne that began the first of six weeks at number one on February 12, 1949. Five days later, she was recording Baby, Come Out of the Clouds for her next specialty appearance in an MGM musical, the Esther Williams picture Duchess of Idaho. This would be her last film as part of the seven-year contract she had signed in 1942. As the film was released in June 1950, Hornes career took several new turns. That month, free of her movie contract, she sailed to Europe for another long tour; she revealed her marriage to Hayton to the press; and her name was listed in Red Channels, a publication intended to inform broadcasters of which performers were Communists or Communist sympathizers. She was not actually called a Communist, but only included because of her association with others, notably Paul Robeson, and because she had assisted various liberal organizations in Hollywood in the 1940s, primarily in connection with their civil rights activities. The inclusion of her name, however, was enough to damage her career significantly. No movie studio offered her another film contract; she was without a recording contract; and there were no offers to appear on radio or the emerging medium of television. Thankfully, she still had live appearances to keep her going, but she worked in Europe increasingly over the next several years. She came back from Europe in September 1950, and in December opened for the first time at the Sands Hotel in Las Vegas, where she would appear annually for the next decade. There were more European trips in 1952 and 1954. Eventually, Horne managed to get herself cleared from the blacklist, and media opportunities in the U.S. opened up again. At the end of 1954, she re-signed to RCA, and she was back in the recording studio in March 1955 cutting a revival of the 1928 Ruth Etting hit Love Me or Leave Me to take advantage of the Etting film biography of the same name due for release that spring. The recording gave her something she had never had before, a hit single; it peaked at number 19 in the Billboard chart in July. RCA quickly followed with a full-length LP, Its Love. Horne began to make appearances on television variety shows, and she was even invited back to MGM to perform in the film Meet Me in Las Vegas. Of course, all she did was sing a song. The movie opened in the winter of 1956, and that year she released more RCA recordings, toured Europe again, and, starting on New Years Eve, opened a long run in the Empire Room of the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York. RCA brought in recording equipment on February 20, 1957, and the result was the live LP Lena Horne at the Waldorf Astoria, released that summer, which reached the Top 25 in Billboard and the Top Ten in Cash Box and was reported to be the best-selling album by a female artist on RCA up to that time. Horne, meanwhile, had moved her show to the Cocoanut Grove in Hollywood in June, where she recorded a live EP, Lena Horne at the Cocoanut Grove, and announced that she was leaving nightclub work temporarily. She was preparing to star in a Broadway musical. The show was Jamaica, with songs by Harold Arlen and E.Y. Harburg, originally written as a vehicle for Harry Belafonte, who proved unavailable. The creators then rewrote it somewhat to beef up the part of the male leads girlfriend for Horne. Critics were not impressed with the show itself when it opened on October 31, 1957, but they were impressed with Horne, who carried the production to a run of 558 performances that continued until April 11, 1959. Based in New York, she issued plenty of new RCA recordings during this period, including an LP called Stormy Weather; the Jamaica cast album; Give the Lady What She Wants (a Top 20 hit in the fall of 1958); a duet album with Belafonte of songs from Porgy and Bess recorded to coincide with the release of a film version of the Gershwin opera in 1959; and Songs by Burke and Van Heusen. Horne disliked the Porgy and Bess LP and even sued RCA to prevent the label from releasing it, but when it came out it made the Top 15 in Billboard and the Top Ten in Cash Box. It also earned her her first Grammy Award nomination for Best Vocal Performance, Female, though she lost to Ella Fitzgerald. Finished with her Broadway commitment, Horne went back to nightclub work in 1959, performing in Europe that summer and fall and returning to the Sands in Las Vegas. Her schedule was much the same in 1960. That November, RCA again recorded her in concert for the 1961 album Lena at the Sands, which earned her another Grammy nomination for Best Solo Vocal Performance, Female, and another loss, this time to Judy Garland, whose Judy at Carnegie Hall also won Album of the Year. Horne next mounted a stage show, Lena Horne in Her Nine OClock Revue, that was intended to go to Broadway but closed out of town after tryouts in Toronto and New Haven. She continued to record for RCA, charting with Lena on the Blue Side in April 1962 and Lena...Lovely and Alive in February 1963 (the latter earning her a third Grammy nomination for Best Solo Vocal Performance, Female, and another loss to Ella Fitzgerald), but diminishing sales led to the end of her contract. She signed to Charter Records and recorded two LPs, Lena Sings Your Requests and Goes Latin (later reissued as a two-fer by DRG Records under the title Lena Goes Latin & Sings Your Requests), but her increasing involvement in the civil rights movement of the early 60s (she appeared with civil rights leader Medgar Evers in Jackson, MS, just before he was assassinated on June 12, 1963, and attended the March on Washington with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., on August 28) led her to question her role as an entertainer. She wrote an article for Show magazine called I Just Want to Be Myself, and it inspired some of her songwriting colleagues to provide her with more politically oriented material. Harold Arlen and E.Y. Harburg sent her Silent Spring, a song that used the title of Rachel Carsons environmentalist book but treated broader social concerns, and Jule Styne, Betty Comden, and Adolph Green wrote the civil rights-oriented Now! to the tune of Hava Na Gila. Horne premiered both at a Carnegie Hall appearance mounted as a benefit for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), where they were heard by a producer at 20th Century Fox Records, who signed her to a new recording contract. A single pairing Now! and Silent Spring made the lower reaches of the pop charts in November 1963 and even made the Top 20 of Cash Boxs R&B chart (Billboard did not publish a separate R&B chart at the time), despite resistance from some radio stations. Horne followed with a recording of Bob Dylans civil rights anthem Blowin in the Wind and the 1964 LP Heres Lena Now! Of course, in early 1964 the Beatles led the British Invasion, which tended to marginalize middle-of-the-road performers like Horne in American record stores. Nevertheless, she did what she could, turning more to television, with a special filmed in England in March 1964 and eventually shown in the U.S. in December, and more appearances on variety shows. She moved to another new record label, United Artists, which released Feelin’ Good in 1965 and Lena in Hollywood, Soul, and the holiday collection Merry from Lena in 1966. After that, she was without a recording contract for a few years. She had also given up performing in the Nevada showrooms, though she continued to play club dates. In 1969, she acted in the Western Death of a Gunfighter, also singing a song over the opening and closing credits. That September, NBC broadcast her first U.S.-originated television special, Monsanto Presents Lena Horne. The same month, she returned to Las Vegas, appearing with Harry Belafonte at Caesars Palace. In October, she recorded a new album for Skye Records accompanied by guitarist Gabor Szabo and issued in the spring of 1970 under the title Lena & Gabor. The LP reached the pop and jazz charts, with a single, Watch What Happens, making the Top 40 of the R&B chart in Cash Box. (Although Horne never considered herself a jazz singer, and jazz critics agreed, she frequently performed and recorded with jazz musicians, and from the 1970s on, she, like other traditional pop singers such as Tony Bennett and Rosemary Clooney, often was lumped in with jazz artists for marketing purposes.) Meanwhile, ABC had contracted with Horne and Belafonte to re-create their stage act for TV, and the result was the special Harry and Lena, broadcast on March 22, 1970, and recorded for a soundtrack album released by RCA. Buddah Records acquired the Lena & Gabor album and reissued it under the name Watch What Happens! The label also signed Horne and had her record a new album, Natures Baby, released in the spring of 1971, on which she covered contemporary pop/rock songs by Elton John, Leon Russell, and Paul McCartney. Unfortunately, by the time the LP came out, she was in no condition to promote it. In a period of just over a year, she had suffered a series of devastating losses. Her father had died at 78 on April 18, 1970; her son had died of kidney failure at 30 on September 12, 1970; and, unexpectedly, her husband, Lennie Hayton, died of a heart attack on April 24, 1971, just as Natures Baby was coming out. She was relatively inactive for a year, but finally began to perform again on a limited basis in March 1972. In 1974, she teamed up with Tony Bennett for a duo act that played in Europe and then came to the U.S., starting with a Broadway run at the Minskoff Theatre that played 37 performances between October 30 and November 24. The two then toured North America through March 1975. She re-signed to RCA yet again and produced two LPs, Lena and Michel, accompanied by Michel Legrand, in 1975 and Lena, a New Album in 1976. She continued to tour in the mid-70s, playing dates with Vic Damone and with Count Basie & His Orchestra. Meanwhile, her son-in-law, film director Sidney Lumet, married to her daughter, Gail, was preparing a movie adaptation of The Wiz, the all-black version of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz that had opened on Broadway in 1975, and he cast her as Glinda the Good Witch. She sang Believe in Yourself in the film and on the soundtrack album, which reached the Top 40 and went gold upon its release in the fall of 1978. Meanwhile, she had starred in a revival of the 1940 musical Pal Joey on the West Coast in the spring of 1978, but the show closed without transferring to Broadway. She continued to make club appearances in the late 70s, but in March 1980 announced her retirement and went on a farewell tour that ran from June to August. But the 63-year-old singer did not retire. Instead, she mounted a one-woman show that she brought to Broadway. Lena Horne: The Lady and Her Music opened at the Nederlander Theatre on May 12, 1981, and was an instant hit. Within a month, she was given a special Tony Award marking its success, and the show played 333 performances, the longest run for a one-person production in Broadway history. The double-LP cast album released by Qwest Records made the pop and R&B LP charts, and it finally won her a Grammy Award for Best Pop Vocal Performance, Female; it also took the Grammy for Best Cast Show Album. After the show closed on June 30, 1982, Hornes 65th birthday, she took it on tour around the country and to London through 1984. At the end of the year, she was a recipient of the Kennedy Center Honors for lifetime achievement in the arts.

Related artists

Lena Horne

Album

- May 18, 2010 Lena Horne Sings: The M-G-M Singles

- January 7, 1941 - June 9, 1958 Stormy Weather, The Legendary Lena 1941-1958

- January 21, 2003 Jamaica, Porgy and Bess

- 2021 The Best Of (All Tracks Remastered)

- 2021 The Remasters (All Tracks Remastered)

- 2020 Christmas Holidays with Lena Horne

- 2018 Once in a While

- 2017 Musical Moments to Remember: Lena Horne – I Sing...! [2]

- 2011 Lena Horne Sings Your Requests

- 2007 Lena-A New Album

- 2007 The Best Of: The United Artists & Blue Note Recording

- 2006 Seasons Of A Life

- 2005 Anthology

- 2005 The Best of Lena Horne

- 2004 Songs by Burke and Van Heusen

- 2002 The Young Star

- 2000 Greatest Hits

- 1999 Love Songs

- 1998 Ev'ry Time We Say Goodbye

- 1998 Being Myself

- 1998 Evry Time We Say Goodbye

- 1996 Aint It the Truth: Lena Horne at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

- 1996 Whispering

- 1995 Merry From Lena

- 1994 We'll Be Together Again

- 1976 Lena, a New Album

- 1971 Nature's Baby

- 1971 Natures Baby

- 1970/2018 Lena & Gabor: Very Truly Yours [2]

- 1964 Lena Goes Latin & Sings Your Requests

- 1962 Lovely & Alive

- 1959 Porgy and Bess

- 1957/1961 Lena Horne: Alive And In Person! At The Waldorf Astoria (1957) - At The Sands (1961)

- 1957 Stormy Weather

Compilation

- 2010 Four Classic Albums Plus

- 2007 The Best Of (2CD)

- 2002 At The Waldorf Astoria (1957) / At The Sands (1961)

- 2001 The Classic Lena Horne

Live album